Bank of England eschews any talk about ‘stagflation,’ but that doesn’t mean it’s not a risk

Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey may not like to talk about a feared economic phenomenon that’s typified by persistent inflation, stagnating output and rising unemployment, but that’s exactly what the central bank pointed toward in its latest outlook even though it ended up cutting interest rates a quarter point to 4.5%.

“I don’t use the word stagflation,” Bailey said in a press conference earlier this month, responding to a question from a journalist about a lackluster economic forecast that used variations of the word “uncertain” 62 times. “It really doesn’t have a sort of a particularly, frankly precise meaning.”

Oh, but it does. The Cambridge Dictionary defines the term as “an economic situation in which prices keep rising but economic activity does not increase,” and it’s exactly the picture emerging from the report. Bailey, in fact, said that UK inflation would actually surge to around 3.7% this year—largely because of rising energy prices due to tight natural gas supplies and a colder-than-usual winter in Europe—before possibly returning to a lower baseline target. The outlook also said that GDP growth—which was zero in the third quarter last year and negative .1% in the fourth quarter—had been weaker than expected amid declining business and consumer confidence and an easing labor market. Unemployment is expected to tip toeup and hit 4.75%.

“If you look at the evolution of the last 12 months…we’ve had an increase in population. I think we’ve had an increase therefore in labour supply. We haven’t had a change in GDP,” Bailey continued. “You can only conclude mathematically that productivity has got much worse.”

‘Disinflation’?

The central banker blamed much of the malaise on an ill-defined “heightened uncertainty” at home and abroad but said growth may resume toward the middle of the year, along with an ongoing “disinflation process” he says has only been temporarily interrupted. That’s the kind of doublespeak that only the wonkiest economists can get away with, and journalists were quick to question possible similarities with the so-called “transitory” inflation of a few years back that turned out to be anything but. Bailey seemingly struggled to respond.

“On the question of, um, temporary and the, the pickup in inflation, the word gradual is, as I said, is in there because there is more uncertainty,” he said.

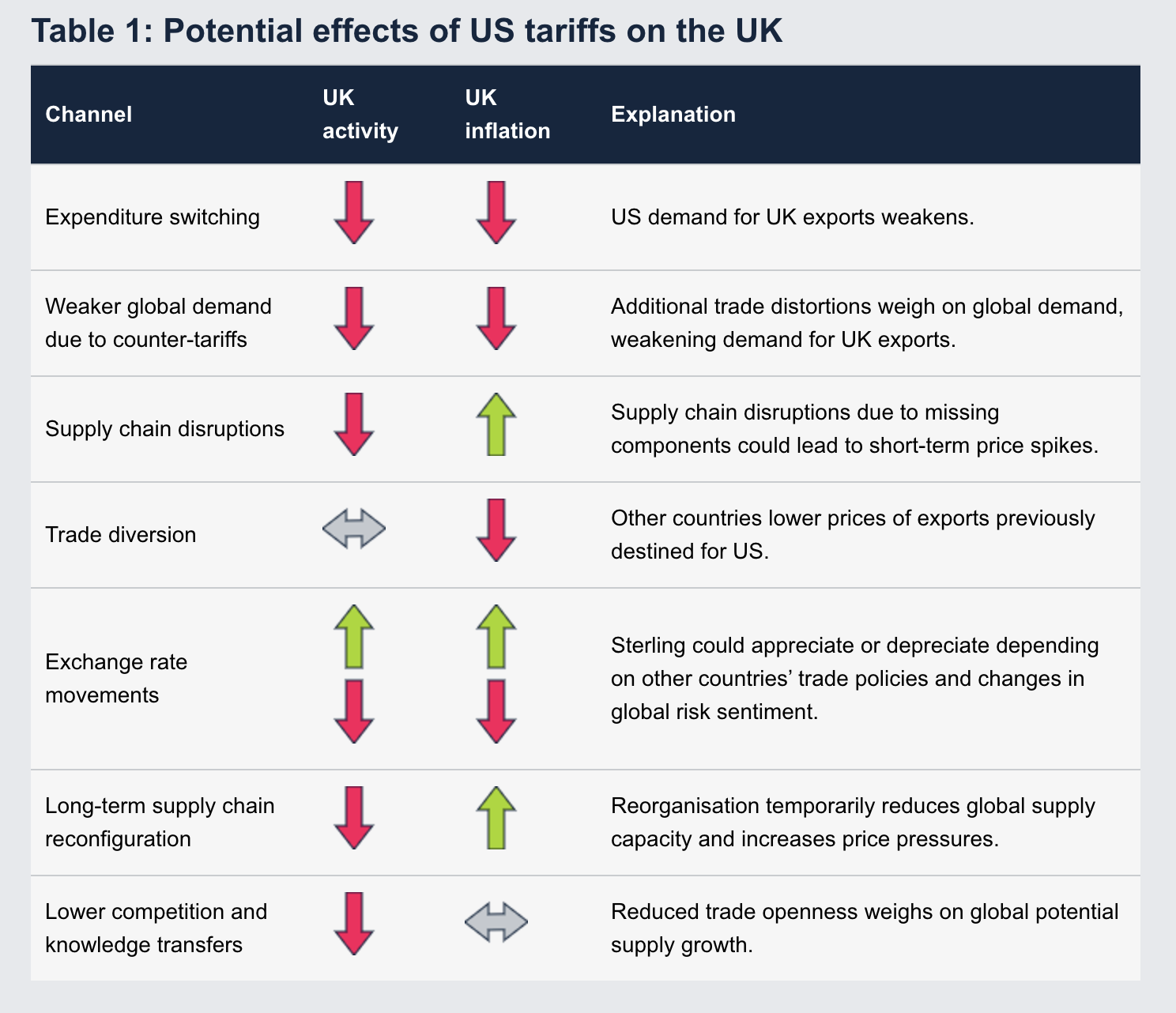

The outlook has many complex, moving parts, however, and perhaps the biggest unknown is just how potential tariffs threatened by the administration of US President Donald Trump could impact the UK economy, and there, once again, the answer is that it all depends. The UK is somewhat protected because 70% of its exports to the US are services, but the bank posted a lengthy infographic showing the ways trade measures could affect inflation, economic activity and the exchange rate.

“I think that if there were to be tariffs that contributed to what I would call a sort of a fragmentation of the world economy, then that would be negative for growth in the world economy,” Bailey said. “Effects on inflation, as we set out in the box, are much more ambiguous, actually…So, we’re very clear in the box that you can’t make a clear and unambiguous, in a sense, prediction on what would happen to inflation in that context, because it depends on a lot of things.”

In other words, please stand by. Whether or not US tariffs are more bark or bite remains to be seen, and recent talks aimed at ending the Russo-Ukrainian War could also lead to an outcome that would see natural gas restrictions ease and prices fall. Or not.

Volatility reigns

In the meantime, traders of the world’s third-largest pair of currencies (GBP/USD) will want to keep paying close attention. While some have taken to social media to bemoan the latest swings—with one commentator on Reddit saying that “the last few weeks have just about broken me”—some context is in order. According to an analysis produced by New York University’s Stern School of Business, volatility has indeed picked up slightly over the past several months, but it’s nowhere near levels seen during previous economic crises surrounding the brief government of Liz Truss in late 2022, the initial period of the COVID pandemic in 2020, and the Brexit vote in 2016.

Despite the latest concerns, the FTSE 100 has actually outperformed the S&P 500 so far this year, rising 6%, and the pound is exactly where it was one year ago. That suggests uncertainty is indeed the name of the game at the moment, and unexpected outcomes could abound. As BMO chief economist Douglas Porter points out, the current class of global economic leaders doesn’t have much real-world experience dealing with the kind of stagflation that last rocked the world from 1965 to 1982. Bailey, for his part, was at the time working on a 478-page thesis at the University of Oxford about the impact of the Napoleonic Wars in the early 19th century on the development of the local cotton industry. Talk about dense.

“Almost no one now making the decisions and/or actively driving the markets has any hands-on experience with true inflation,” BMO’s Porter wrote back in 2022. “Thus, almost by definition, mistakes will be made. And, thus, every commentator, analyst, and pundit should be somewhat humble about their ability to predict what is going to unfold.”

That’s some real uncertainty, and knowing that, the best advice may be the simplest (and the most British): Keep calm and carry on.